- ZeroBlockers

- Posts

- Why We Work the Way We Work: The Industrial Legacy of Modern Work

Why We Work the Way We Work: The Industrial Legacy of Modern Work

The way we work today is not an accident of history, but rather a carefully designed system born in the factories of the 20th century. To understand our modern work practices—from organisational hierarchies to performance metrics—we must look back to the revolutionary ideas of Frederick Taylor and the profound impact of industrial manufacturing on workplace organisation.

At the turn of the 20th century, work was primarily performed by craftspeople who maintained complete control over their production processes. Each craftsperson would build entire products from start to finish, using methods passed down through generations. This changed dramatically when Frederick Taylor introduced "The Principles of Scientific Management," revolutionising how work was organised and managed.

Taylor's approach wasn't merely a new management philosophy—it was a complete reimagining of work itself, designed to maximise efficiency in an era of mass production. But why did these principles take such deep root, and why do they continue to influence our work practices even in the digital age?

The Context That Shaped Scientific Management

Guaranteed Markets and the Drive for Efficiency

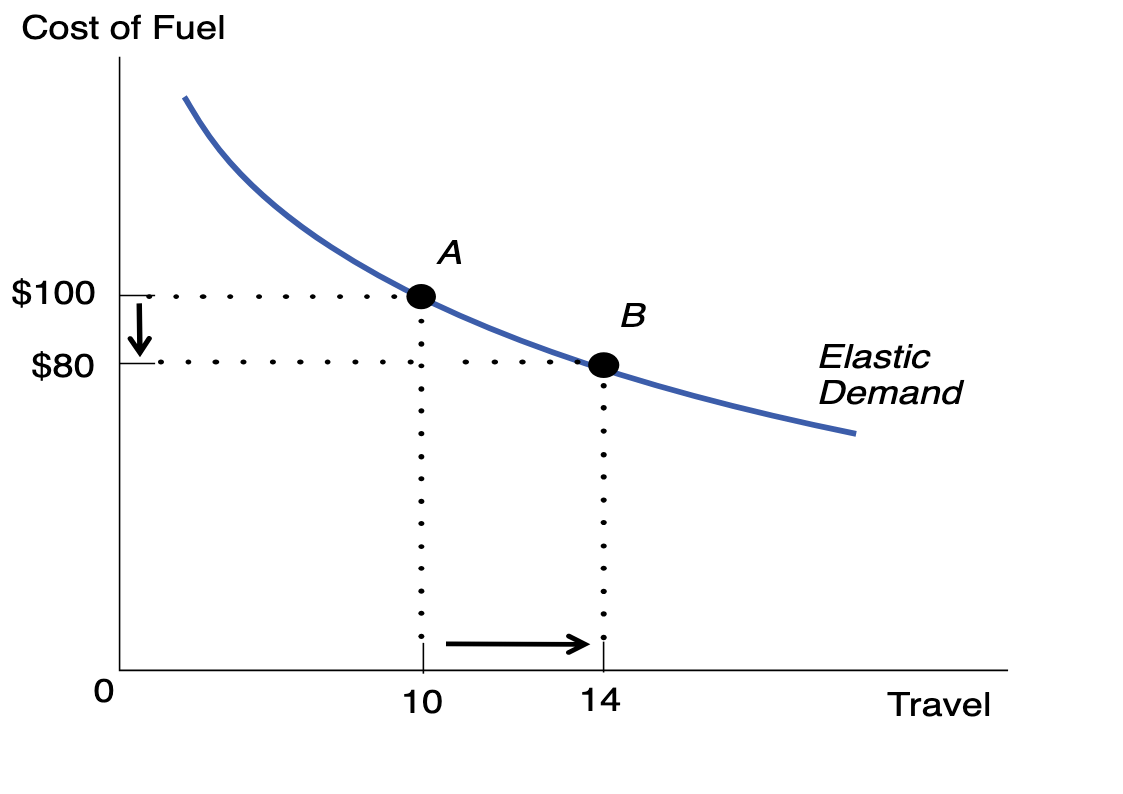

At the time, the market for goods such as cars, furniture, and clothing was nearly guaranteed. Demand was elastic—meaning that the cheaper products became, the more people would buy. This created a singular focus: efficiency. The companies that could produce goods at a lower cost would dominate the market. Taylor's principles were designed to maximise efficiency by standardising processes to eliminate waste and optimise worker productivity.

The Stability of Products

Another key factor was the infrequency of change. Most products remained the same for years, even decades. Henry Ford’s Model T, for instance, remained largely unchanged for nearly 20 years. This stability allowed companies to prioritise efficiency over adaptability. They could afford to create specialised departments and functions, even though this made organisational change more difficult because the efficiency gains outweighed the infrequent cost of change.

A Workforce That Followed, Not Questioned

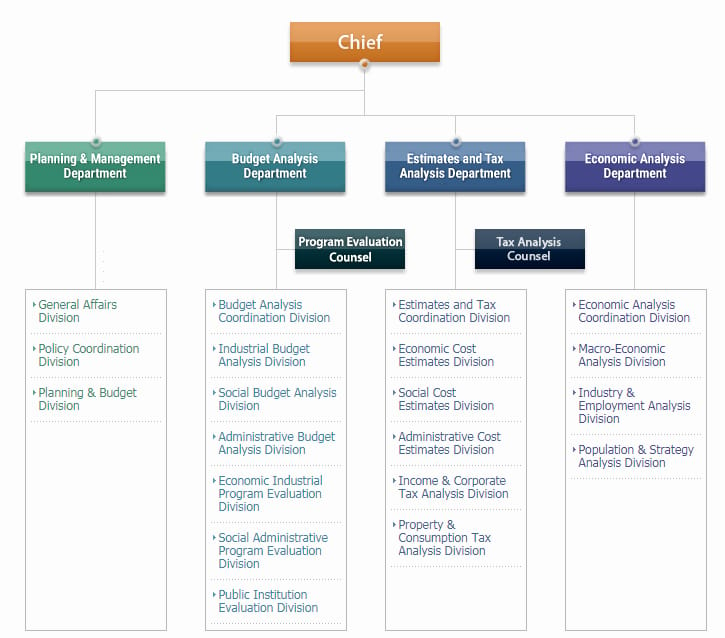

At the time, most factory workers had little formal education. They were not hired for their ability to think critically or problem-solve but rather for their ability to follow instructions. Managers were needed to design detailed processes that uneducated laborers could follow without deviation or questioning. This division between "thinkers" and "doers" gave birth to the organisational chart as we know it today, with its clear delineation between management and workers—a structure that persists even in knowledge-based industries where all workers are highly educated.

Metrics: Measuring Output Like a Factory

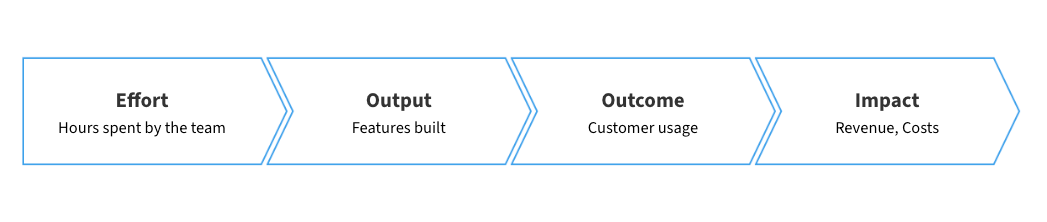

Factories had a straightforward relationship between hours worked and output produced. The longer a worker spent assembling widgets, the more widgets they produced.

Since manual labor was physically demanding, workers might naturally seek to pace themselves if not monitored. This led to the implementation of output targets and performance tracking—practices that we still use today, even in creative and knowledge work where the relationship between time and output is far more complex.

However, division of labour means that you cannot hold people accountable for the outcomes of what they are building. If they do their job but the product fails it is not their fault. This is why we still have an output focus even when faced with the fact that most features and products fail to deliver the expected business value.

Four different metrics types: Effort, Output, Outcome and Impact.

Utilisation as the Holy Grail

Another key principle of factory efficiency was machine utilisation. The longer a machine was running, the lower the cost per unit produced. Idle time was wasteful. This belief extended to workers: if someone wasn’t actively engaged in a task, they were perceived as inefficient.

In the software industry, this manifests as the pressure to always be coding or working on visible tasks. But high utilisation can be counterproductive in knowledge work. Without slack in the system, there’s no time for problem-solving, innovation, or responding to unexpected challenges. Nevertheless, the factory-inspired mindset persists, driving businesses to maximise short-term output at the cost of long-term adaptability.

If you have a separation of work it is unlikely that every step will take the exact same amount of time to complete. This means that you need backlogs to ensure that the system can continue to operate at a consistent pace. But backlogs cause a system to slow down because work spends the majority of it’s time in the backlog rather than being processed. Backlogs also suck up cash flow and mask faults in the system, multiplying their cost.

This means that by focusing on utlisation we can actually hurt the efficiency of the system.

The Digital Revolution and the Legacy of Scientific Management

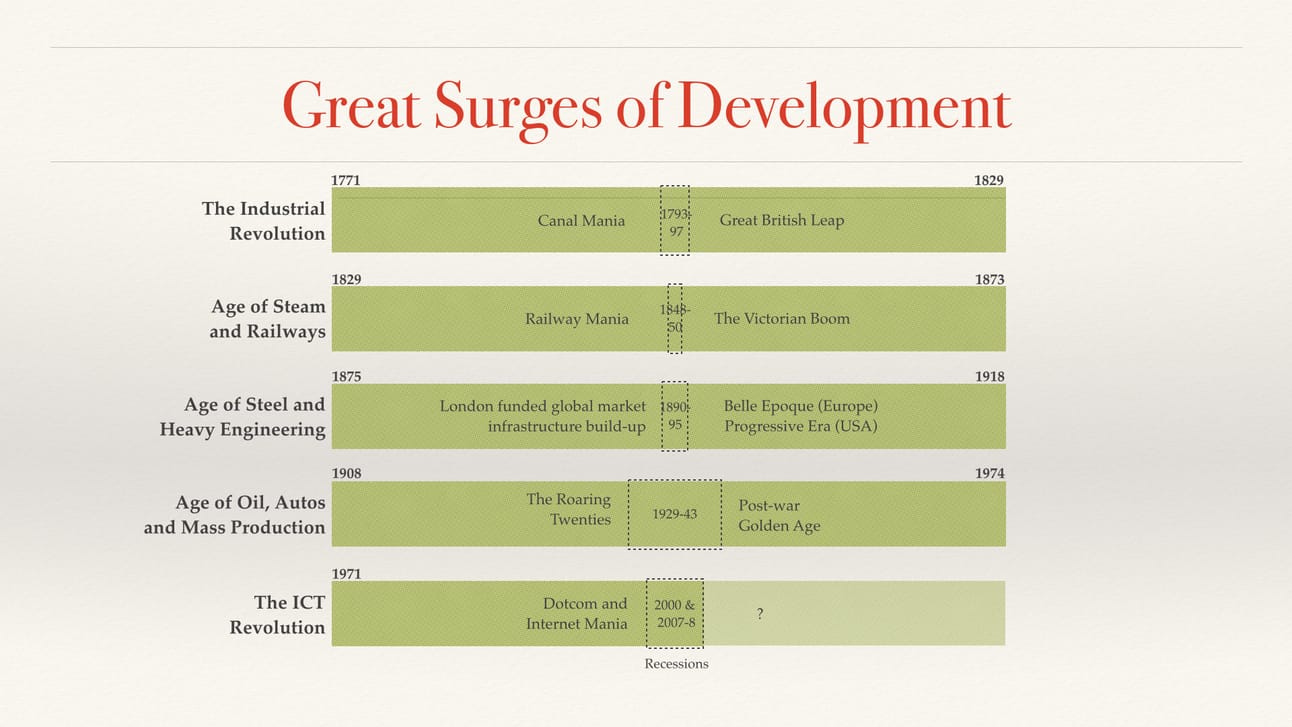

The economist Carlota Perez's work on technological revolutions provides crucial insight into our current predicament. Perez identifies five major technological revolutions since the Industrial Revolution, each bringing fundamental changes to how society organises work and creates value. We are now in the midst of the fifth revolution—the age of information and telecommunications—yet many of our management practices remain stuck in the fourth revolution of mass production.

According to Perez, each technological revolution follows a similar pattern: an installation period where the technology spreads rapidly, followed by a turning point of restructuring, and finally a deployment period where society fully adapts its institutions and practices to the new paradigm. Software development and digital transformation represent the core of this latest revolution, demanding fundamentally different approaches to work organisation.

Yet industrial-era practices remain deeply ingrained in business thinking. Our organisational charts, departmental structures, performance metrics, and utilisation targets all bear the unmistakable imprint of Taylor's scientific management principles. The conditions that made these practices effective in the industrial era have fundamentally changed. Today's knowledge workers are highly educated and capable of complex decision-making. Product cycles are measured in weeks or months, not years. Market demands shift rapidly, requiring organisational agility over rigid efficiency. The relationship between time and output in creative and knowledge work is non-linear and often unpredictable.

There will always be pushback against changes because the current system is functioning well enough to keep organisations afloat, and change might have unexpected consequences. This is where Chesterton's Fence comes in—cautioning against removing something without understanding why it was put there in the first place. We need to understand how our current practices came to be before we discard or modify them. By viewing our practices in the historical context in which they were developed and the conditions they were designed to address, we can better evaluate their relevance to our current work realities.

Despite mounting evidence of inefficiencies in software development, many organisations continue to operate using management principles designed for a world of mass production. Understanding both the historical context of these practices and Perez's framework of technological revolutions is crucial for modern leaders who wish to evolve their management approaches to better suit contemporary work realities.

Looking Forward

Software development today is incredibly inefficient and ineffective, and it is down to the processes that we are using. The most successful organisations are shifting away from the practices that worked in mass-manufacturing to ones that work for the era of software: empowered teams with outcome-based metrics.

The future of work may require us to unlearn much of what we inherited from the industrial era. But this can only happen if we first understand why we work the way we work—and consciously choose which parts of that legacy to carry forward into the future.